Promise Over Performance

A Lutheran Critique of John MacArthur’s Gospel

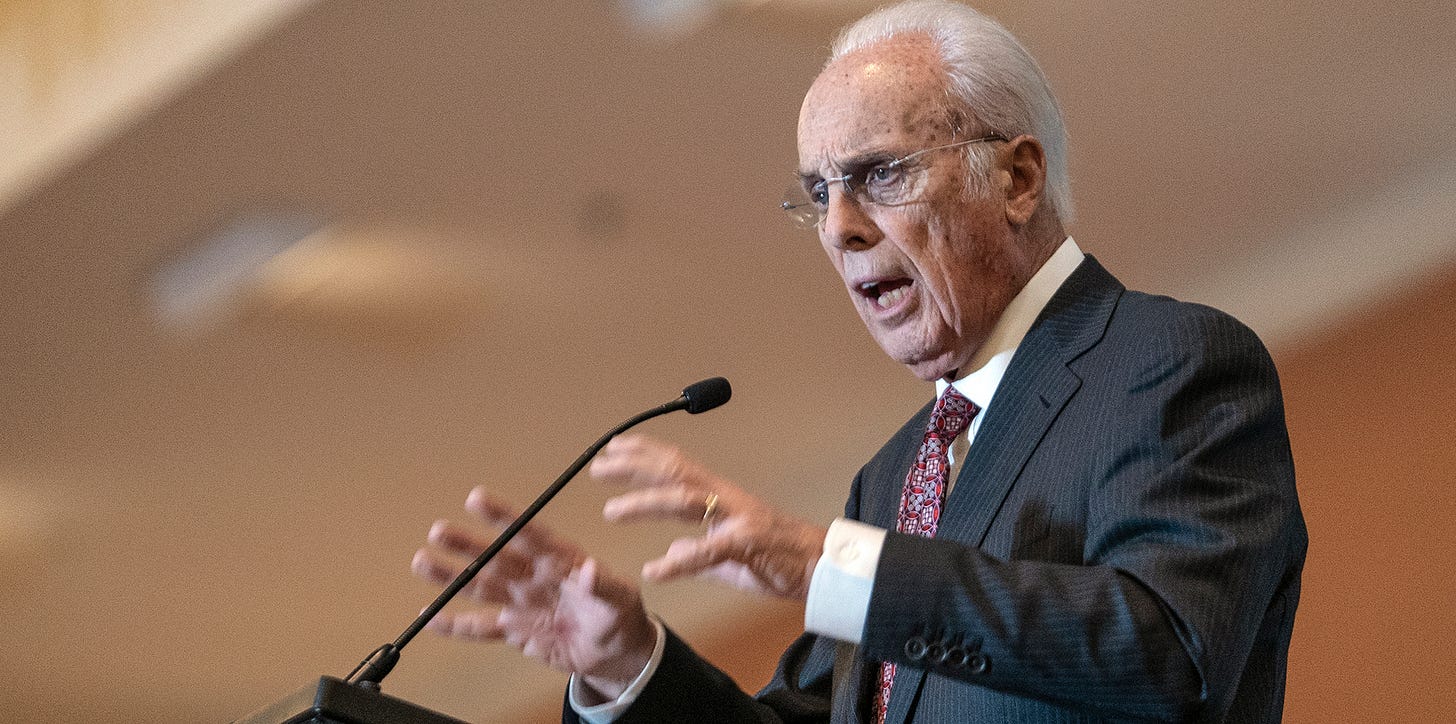

The recent passing of John MacArthur, a prominent evangelical pastor, author, and teacher, has prompted many within the Christian community to reflect on his life and legacy. MacArthur, who served as pastor of Grace Community Church in Sun Valley, California, for over five decades, was a towering figure in modern evangelicalism. His commitment to exposi…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Word Alone to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.